Alifah NurFeatures9 months ago106 Views

A house is not just a place to crash after a long day, it’s security, stability, and the foundation of a thriving community. It’s where children grow up, having neighbours become friends, neighbourhoods are also where a nation shows their commitment to its people. But here is the problem: in most of the cities around the world, housing crises are turning that dream into a distant fantasy. Home prices are skyrocketing, rental markets are ruthless, and the idea of owning a home feels about as realistic as winning the lottery.

Singapore, a tiny city-state that went from overcrowded slums to one of the world’s most efficient and affordable public housing systems. Nowadays, over 80% of Singaporeans live in government-built homes, and more than 90% own them. In contrast, in New Zealand, especially in Hamilton, the housing market is swiftly escalating and faces significant challenges in housing affordability and homeownership. Recent data indicates that Hamilton has the lowest homeownership rate among New Zealand’s territorial authorities, with only 53.5% of residents owning their homes (Bridge Housing New Zealand Herald). This low rate reflects broader national trends, where rising property prices and rental costs have made homeownership increasingly elusive for many Kiwis, and people are left wondering…

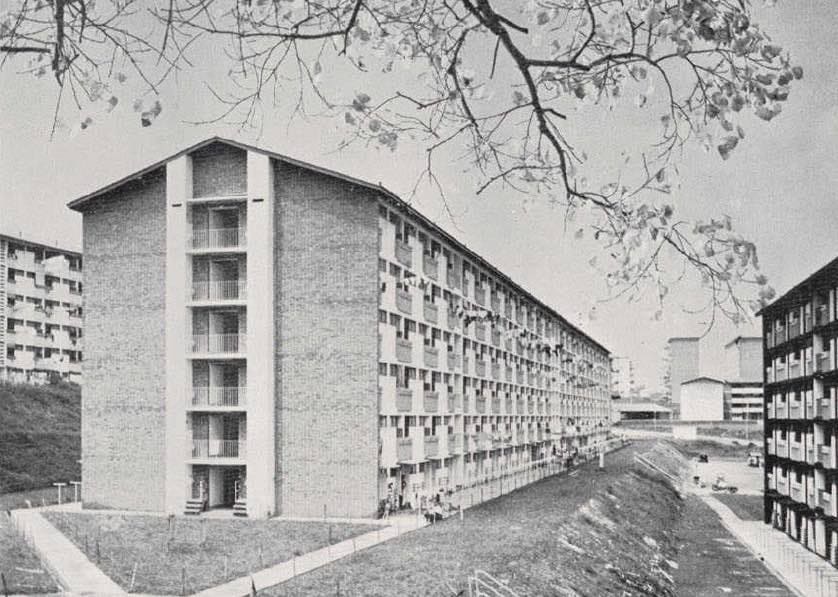

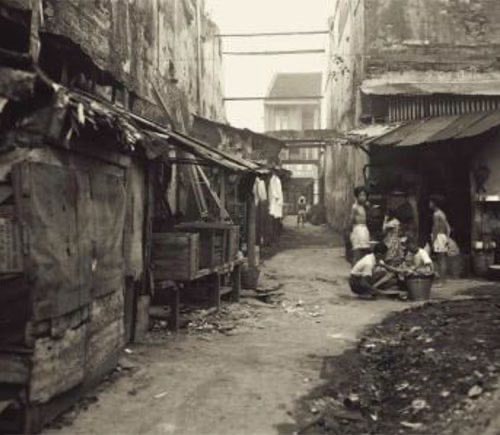

Singapore’s success was not just luck. In the 1960s, the country faced a full-blown housing disaster. There were overcrowded slums everywhere, public health was at risk, and social stability was precarious. The government did not just acknowledge the crisis, they tackled it head-on by creating the Housing and Development Board (HDB) in 1960. The subsequent actions amounted to a remarkable feat in urban planning. With aggressive intervention, rapid development, and a focus on homeownership, Singapore made sure its citizens had affordable, high-quality housing. Comparing this issue to New Zealand, which has taken a more passive approach, hoping the private market will just ‘figure it out’, while housing prices continue their wild climb.

One of the secrets behind Singapore’s success is its commitment to smart urban planning. HDB estates are not just clusters of apartment buildings, they are self-contained communities. Schools, healthcare centres, parks, public transport, and shopping districts are built in these neighbourhoods, making life easier and reducing urban congestion. Compare this to Hamilton, where urban sprawl is increasing commute times, infrastructure struggles to keep up, and affordable housing options are being pushed further and further away from city centres.

The difference? Singapore has plans for people to live, work, and play in their neighbourhoods

New Zealand? It often feels like cities just expand with no real long-term vision.

Of course, New Zealand and Singapore are vastly different places. Singapore is a dense, highly regulated city-state. However, this does not preclude us from gaining valuable insights. The housing challenges Hamilton faces today with rising costs, limited affordable options, and a rental market that leaves many families in a state of permanent uncertainty, reflected what Singapore overcame decades ago.

One of the biggest differences between the two countries is homeownership policy. In Singapore, the build-to-order (BTO) system allows first-time buyers to purchase subsidised flats at affordable rates; this means more people actually own their homes instead of endlessly renting them. In contrast, New Zealand has focused almost entirely on rental-based public housing. While this provides short-term relief, it does little to give people long-term security. The cycle of renting continues, and many families remain locked out of the housing market altogether.

What if New Zealand shifted its focus toward ownership rather than just providing state-owned rental properties? Imagine a system where young families could buy affordable homes with government assistance rather than being stuck in an endless loop of renting. Would this not create more financial stability and give people a real stake in their communities?

Another area where Singapore shines is social integration. Its Ethnic Integration Policy (EIP) ensures that government-built housing reflects the nation’s diversity, preventing the formation of ethnic enclaves. This policy has helped foster national unity and social cohesion. However, in New Zealand, housing is still largely segregated by economic and ethnic lines. A major factor driving social segregation in New Zealand is the stark disparity in homeownership rates among ethnic groups. Historically, Māori and Pacific peoples have faced systemic barriers to homeownership, including lower average incomes, limited intergenerational wealth, and higher reliance on rental housing. According to the 2013 Census, Māori households had a homeownership rate of just 28.2%, Pacific households had an even lower rate of 18.5%, European households, by contrast, had a significantly higher homeownership rate of 56.8%, and Asian households had a rate of 34.8% based on Te Ara Research New Zealand Government.

These figures illustrate a housing system where Māori and Pacific communities are still disproportionately excluded from homeownership, forcing many into the rental market, where they face higher housing costs and instability. This lack of access to homeownership perpetuates wealth gaps, as property ownership remains one of the most significant pathways to financial security and intergenerational wealth. Due to this condition, it could greatly benefit Hamilton to create proactive policies that promote mixed-income and multicultural neighbourhoods, ensuring that affordable housing does not become synonymous with economic hardship.

Real estate speculation is a significant issue. Singapore has taken decisive steps to control property speculation, implementing measures such as the Additional Buyer’s Stamp Duty (ABSD)| and loan-to-value (LTV) restrictions to prevent investors from driving up prices. This ensures that public housing remains affordable for those who actually need a place to live, not just for those looking to make a quick profit.

New Zealand, on the other hand, has been largely reactive, allowing both domestic and foreign investors to drive up prices, leaving first-home buyers behind. New Zealand cities have seen property values surge because investors keep outbidding regular buyers.

Could adopting similar cooling measures as Singapore help regulate this madness? If first-time buyers didn’t have to compete with profit-driven investors, perhaps homeownership wouldn’t feel like an impossible dream.

But sustainability is another major concern. Singapore has been integrating eco-friendly designs into its public housing for years, with solar panels, rainwater harvesting, and green rooftops helping to reduce energy consumption and environmental impact.

Meanwhile, New Zealand’s approach to sustainable housing has been… inconsistent. Some developments embrace eco-friendly solutions, but there’s no widespread, systematic effort to make sustainability a core feature of public housing.

Imagine if Hamilton’s new public housing projects were designed with solar-powered energy grids, smart water-saving systems, and urban green spaces. Not only would this help reduce long-term costs for residents, but it would also contribute to New Zealand’s broader environmental goals.

Could a shift toward sustainable, smart housing be the key to ensuring that future generations aren’t stuck dealing with today’s housing mess?

Singapore’s public housing success is proof that a housing crisis doesn’t have to be permanent. The key is a bold, forward-thinking policy that prioritises long-term stability over quick, short-term fixes. If New Zealand moved away from a rental-heavy public housing model towards subsidised homeownership, integrated essential services into new developments, regulated market speculation, and prioritised sustainable infrastructure, housing could become more of a success story than a crisis.

Do we actually have the political will to make it happen? Or will we continue relying on Band-Aid solutions while housing prices soar beyond the reach of everyday Kiwis?

The future of affordable, stable, and sustainable housing in New Zealand doesn’t have to be a dream. Singapore has shown that with the right policies, it can be a reality.

If a tiny city-state with no natural resources could solve its housing crisis, why can’t a country as vast and resource-rich as New Zealand? Maybe it’s time to stop making excuses and start making real changes before homeownership in Aotearoa becomes nothing more than a distant memory.

Features3 months ago

Features3 months ago

Columns3 months ago

Columns3 months ago

Columns3 months ago

Columns6 months ago

Columns3 months ago

Columns3 months ago

Columns3 months ago

Columns6 months ago