“The public is conditioned to accept negative images of the Māori. The values and worth of Māori people are continually overlooked.” – Merata Mita

Māori film-making is changing – and I don’t mean to be so damn dramatic about that, but with the influx of mainstream media influencing our mahi-toi, why wouldn’t we consider this influence as a form of adaptation? For many, the only portrayal of Māori in film was through the likes of ‘Once Were Warriors’ and ‘River Queen’, films that were made for the outward eye, for the general public to look in on in amusement as they struggle to connect with those ‘savage people’ that were here first. This isn’t any hate to Pākehā, but a testament to the filmmakers that are breaking a cycle of Pākehā serving cinema.

Merata Mita, in case you aren’t aware, is a pioneer of Māori cinema and an important figurehead for the development of who Māori are in film today. Mita was the first indigenous woman and the first woman in Aotearoa New Zealand to solely write and direct a dramatic feature film, with her production of Mauri (1988). I shouldn’t have to explain to you the significance of why this is so important or what that meant for wāhine Māori filmmakers and those in film. You now have the likes of Chelsea Winstanley, Ainsley Gardiner, Briar Grace-Smith etc. Wāhine who are powerhouses in their fields, breaking the chain of unsuccessful ventures and telling important stories.

Waru (2018)

If you haven’t watched this film, please click away from this article and come back once you have. Waru, while juvenile in its production, is an amalgamation of kōrero paki from 8 wāhine Māori, told through the same central focus of child abuse. It’s told beautifully through well-crafted cinematography and generally impressive ‘hide the lead’ storytelling. The directors involved were; Ainsley Gardiner, Casey Kaa, Renae Maihi, Awanui Simich-Pene, Briar Grace Smith, Paula Whetu Jones, Chelsea Winstanley & Katie Wolfe. Their names, along with their storytelling, are compelling – carrying so much mana as they understood the importance of Waru and the lives it would ultimately touch.

Waru is an exceptional love story about the lives of children lost to violence or neglect in a broken system. Growing up, my life could be told through some of the shorter segments in the film – specifically the Mum with WINZ on the phone, struggling to find kai for her tamariki but holding her own as she continues to fight. As Māori, we understand the pain through shared wairua, that’s why films are significant for telling our stories. But not as a call to action, looking for white saviours to power through and uplift us in an effort to appease their guilt. Instead, as testaments to the strengths of our people in their stories.

Whina (2022)

Now to take a moment and praise some of our Wāhine Māori actresses. Their performances on and off screen are shaping our current interpretation of the visual arts. Before having seen Whina, I just knew in my soul that Whaea Rena Owen and Aunty Miriama McDowell were going to bring the house down with their performances. But what I wouldn’t expect is the retelling of a story I knew, though told through the impression of Paula Whetu Jones and James Napier Robertson – two terrific directors who brought the entire piece to life. The importance and relevance of seeing Aotearoa’s history play out through the lens of Māori is something that shouldn’t even be in question. I’ve failed to mention Tioreore Ngatai Melbourne, as she is slowly becoming one of my favourite wāhine Māori on screen. Playing against battle veterans in a film that doesn’t stop to let you breathe, it’s relentless in its storytelling, allowing Dame Whina’s story to ring true for us all.

This is one of those films that sits with you, not because of the heavy nature, but the value in performance. There’s a genuinely stellar cast with James Rolleston making an appearance, reminding us why we loved the bright eyed boy from so many years ago. Whina is a dramatic piece, that much is true, but it’s an important piece of history that needed a freshen up and to get slapped with an Auteur touch of approval. One thing I’ll recommend is, take some damn tissues my bro.

Cousins (2021)

Far out, I didn’t expect for Cousins to become such an integral part of film history as a film solely about whānau, but it changed my impression on countless issues regarding storytelling and how language is used. Cousins is told through a very impure non-linear kōrero paki, the timeline bouncing through childhood and into adulthood. It’s not an Arrival timeline, where the edges are blurred, but it’s fractured as a response to the broken psyche of Mata (Tanea Heke). The film is about 3 cousins and their intertwining lives, how they became who they are in connection to each other. That connection is strong enough to span their lifetimes, demanding them to reunite. The film is held together by one of the strongest casts, but made by the aforementioned Briar Grace-Smith and Ainsley Gardiner. By now I’m sure you’re sick of hearing me rattle on about the wāhine Māori filmmakers that make up our film industry but it’s just because they’re that fucking good.

Cousins is an important film for Māori that were raised in the lost generation, helping them to heal some of the damage done thanks to the Government and their attempt to stamp out the embers of a once strong people. But the film, and history, is proof of Māori resilience. They understand wairua and connection to the whenua more than those who are not of this land. Mata, Makareta and Missy represent the backbone of Māori and they show the strength we hold when we come together. Grace-Smith and Gardiner are a dream team, weaving their Auteur spirit into the film and creating a visually stunning mahi toi that is appreciated in all facets.

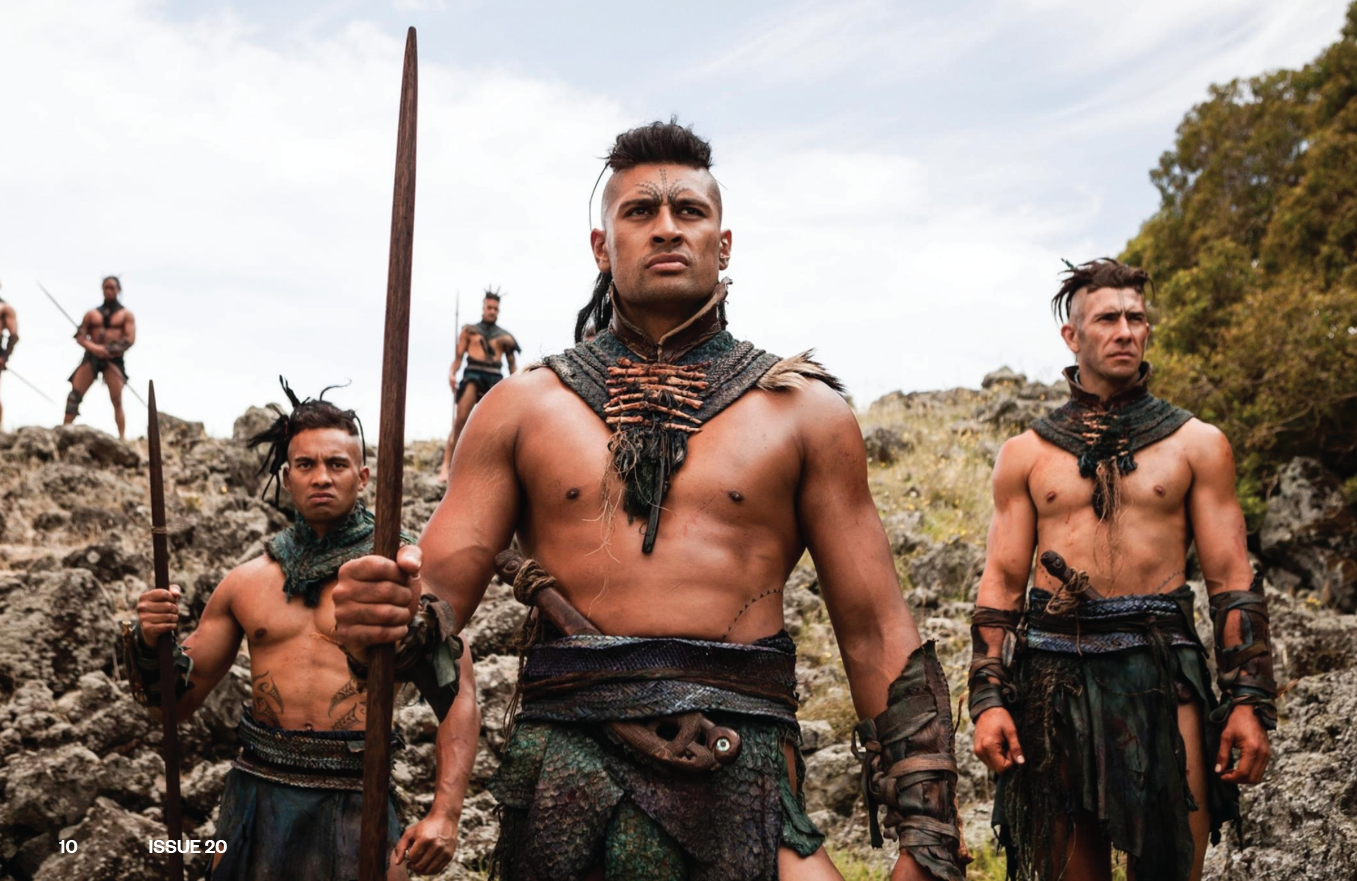

The Dead Lands (2014)

Films in complete Te Reo Māori seem daunting. Shit I reckon they would’ve struggled to find the funding to create this, but the result is nothing short of breath-taking excellence. The Dead Lands is the story of Hongi fighting to avenge the murder of his Pāpā at the hands of a brutal iwi who invade their marae. This film is fucking relentless, and it’s just action packed from hilt to hilt. Throughout the film you can’t help but hold your breath at some of the more claustrophobic shots, understanding the anxiety of Hongi as he battles mental strength against that of Lawrence Makoare’s The Warrior. Fijian director, Toa Fraser, heads the production and what a masterful production it is. The appreciation Fraser has for the Māori process, and understanding kaupapa around it, is just a testament to the respect polynesian tangata have for one another.

I thought it pertinent to mention a non-māori filmmaker and their producing of predominantly (arguably solely) Māori works. There’s an age-old argument in Journalism of who can write about what. But there’s a quote from Rosie Remmerswaal “Sometimes I say, ‘Kāore ōku toto Māori, engari ko Aotearoa te whenua i whakatipu mai i a au. I don’t have any Māori blood, but Aotearoa is the land that raised me.’” There shouldn’t be an issue when it comes to helping and aiding in the production of Māori works – within reason. With The Dead Lands, Fraser had a production team of Māori a mile long, has a deep understanding of kaupapa Māori and understands the plight of Māori. Do I think that there was a Māori capable of producing the film to the same, if not better, quality? Absolutely! But diminishing the value of Māori stories being told on a global stage seems counterproductive.

Now you see, this entire piece is an ode to the power in Māori film-making and kōrero paki. As an aspiring Māori artist (formerly film-maker, looking at you Te Iwi o Te Awa) I find great value and pride in watching, and supporting, the efforts of Tangata Whenua. Someone very close to me once said,

Waiho i te toipoto, kaua i te toiroa

(Let us keep together, not far apart)

Māori filmmaking is something that is under-appreciated – but it’s something that is right there. So just get out of your head and start delving into the great world that is Māori cinema, you won’t regret it e kare.