IS CRIME TRULY AN INDIVIDUAL ISSUE, OR IS IT FUNDAMENTALLY LINKED TO ISSUES OF RACE AND STRUCTURAL INEQUALITY?

Introduction:

Discussions about crime often focus on personal choices or isolated incidents, yet a deeper examination of crime statistics across colonised and/or diverse countries uncovers persistent racial patterns that demand attention. Data from these regions show that certain racial groups are overrepresented in prison populations compared to their share of the general public. These disparities do not occur by accident; they often reflect broader social and historical forces like systemic discrimination, unequal economic opportunities, and biased policing. By examining root causes, we are forced to ask: are crime and punishment fundamentally shaped by racial dynamics embedded within our societies?

The Three Main Causes of Crime and Their Racial Dimensions:

1. SOCIOECONOMIC INEQUALITY

Socioeconomic inequality is one of the most well-established predictors of crime, particularly in societies with pronounced gaps between the wealthy and the poor. When individuals and entire communities lack access to well-paying jobs, quality education, and stable housing, their economic vulnerability can set the stage for higher crime rates. This is not merely theoretical—research consistently shows that societies with wider gaps between rich and poor also experience more social problems, including drug abuse, lower educational attainment, poorer health outcomes, and a greater prevalence of crime. Classic studies have linked resource deprivation with violent crime, arguing that the sense of relative deprivation—comparing personal or group circumstances unfavourably to those of others—can provoke frustration and a greater likelihood of engagement in criminal behaviour.

New Zealand’s experience provides a stark illustration of this connection. In a 2010 national survey, sizeable percentages of Māori (18%) and Pacific peoples (28%) reported not having enough money to meet every day needs, a rate much higher than their European peers. The median income for Māori and Pacific people lags behind that of Europeans, and Pacific people face enduring disadvantage in jobs and housing. Such conditions breed environments where crime becomes, for some, a survival strategy, particularly when legitimate pathways to social mobility are blocked. The correlation between inequality and crime is not unique to New Zealand; studies internationally reveal similar patterns, with economic inequality driving up not just property crime but violent offenses as well.

Racial minorities experience disproportionate poverty due to historical and ongoing discrimination, limiting their opportunities and exposing them to environments where crime risk is high. This is why addressing crime requires more than punitive approaches; it necessitates confronting the root causes of disadvantage that are clustered, often by design, within certain racial communities.

2. DISCRIMINATORY POLICING AND JUSTICE SYSTEM PRACTICES

Systemic bias in law enforcement and the broader justice system is a powerful driver of racial disproportionality in crime statistics and incarceration rates. Discriminatory policing includes practices such as racial profiling, targeted surveillance in minority neighbourhoods, and uneven application of stop-and-search procedures. Minority communities—particularly Black and Pacific peoples in nations like the USA and Aotearoa—are more frequently stopped, searched, arrested, and prosecuted, sometimes regardless of crime rates. For example, in the UK, the Lammy Review revealed that Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) individuals were consistently treated more harshly at every stage, from initial police contact through sentencing, costing taxpayers hundreds of millions and deepening cycles of disadvantage.

The impacts are profound: being over-policed and unfairly charged increases the likelihood of conviction and incarceration, setting off a cascade of disadvantages including unemployment, family disruption, and reduced social mobility. In New Zealand, similar patterns are evident, with Māori and Pacific peoples accounting for significant portions of those charged and imprisoned, far in excess of their presence in the general population. Once within the system, minorities also face barriers to fair trial—including less access to legal aid, systemic suspicion from authorities, and cultural misunderstandings.

These patterns entrench mistrust between minority communities and law enforcement, making it less likely that victims will report crimes or cooperate with police. The resulting feedback loop not only perpetuates overrepresentation in criminal justice systems but can also reinforce public stereotypes about inherent criminality in certain racial groups. Ultimately, this reality helps explain why efforts focused solely on harsher policing or tougher sentencing often worsen racial disparities in crime and imprisonment, rather than reducing them.

3. STRUCTURAL AND SYSTEMIC RACISM

Structural or systemic racism refers to the embedded policies, practices, and historical legacies that continue to disadvantage certain racial groups, even in the absence of explicit bigotry. This operates across multiple domains–housing, education, employment, and, crucially, the criminal justice system. For instance, housing discrimination relegates many Māori and Pacific communities in New Zealand, and Black communities in the UK and US, to areas with poorer schooling, higher unemployment, and more heavily policed public spaces.

These disparities are not accidental—they are the cumulative product of historical injustices, such as colonisation, segregation, or lack of equitable policy interventions. Over time, the effect is to create “neighbourhood effects” where concentrated disadvantage becomes self-perpetuating: poor infrastructure, struggling schools, higher unemployment, and greater police scrutiny all intersect to raise both the risk and rates of crime. For example, in Aotearoa, decades of discriminatory social, housing, and economic policies produced persistent inequalities in health, employment, and wealth for Māori and Pacific people.

The justice system itself can embed and amplify these effects. Laws and policies that seem race-neutral on the surface can nevertheless have “disparate impact,” meaning they hurt minorities more—whether through sentencing guidelines, bail conditions, or rehab opportunities. Systemic racism is why even as explicit legal discrimination has declined, the structural patterns of disadvantage and overrepresentation in prisons remain.

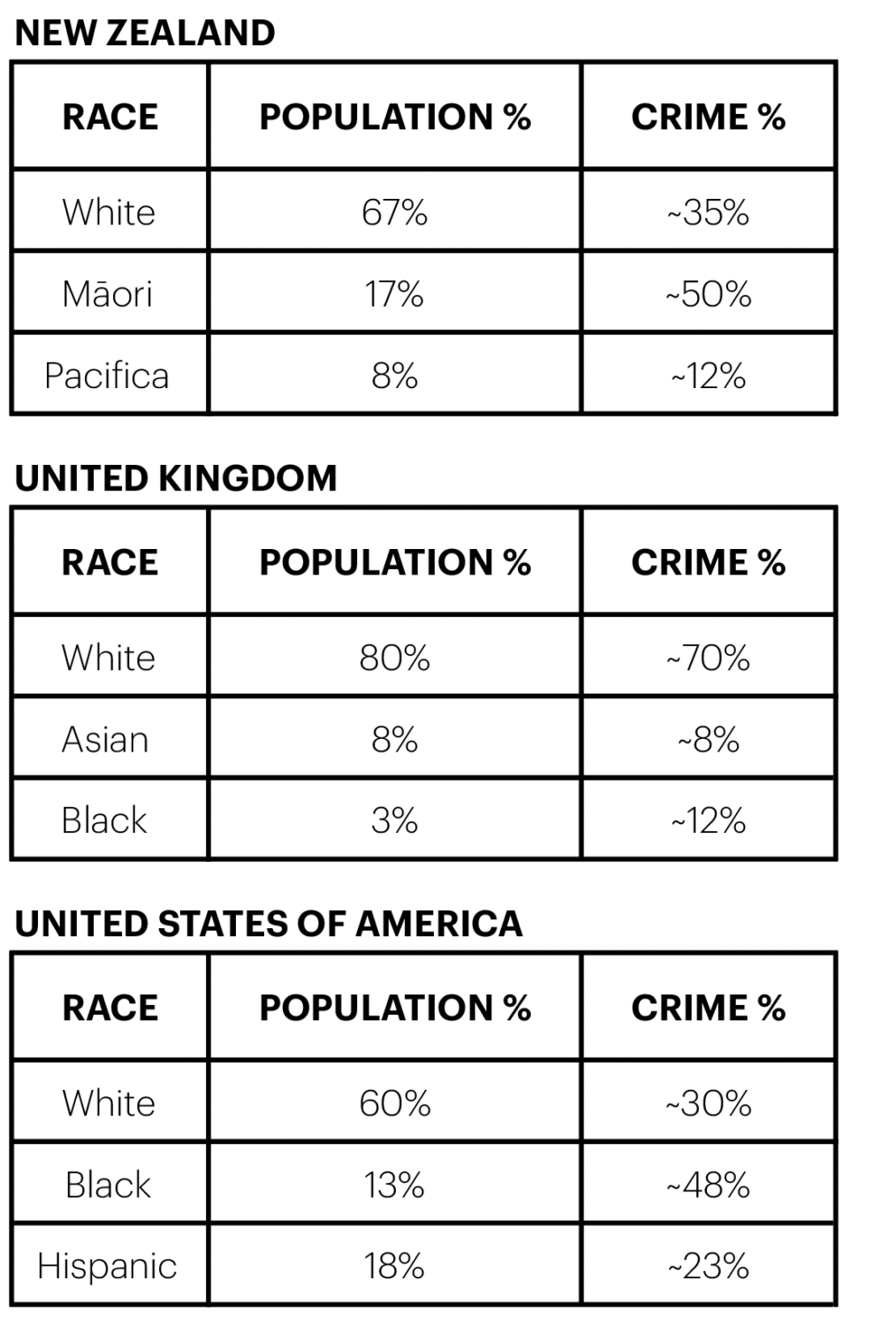

Summary Table: Top 3 Races in Population and Prisons

These comparisons make it clear: racial inequality remains embedded in the justice systems of New Zealand, the United States, and the United Kingdom, as seen through stark overrepresentation of minorities in prisons. In each of these nations, White is the majority race, yet have a disproportionate prison population leaving higher percentages to BIPOC.

Conclusion

The evidence across countries like Aotearoa, the United States, and the United Kingdom compellingly demonstrates that crime cannot be understood solely as a matter of individual wrongdoing. Instead, the persistent and stark overrepresentation of minority groups—particularly Māori, Pacific, Black, and Hispanic peoples—in prison populations reveals deep-seated structural inequalities and racialised dynamics at play. Socioeconomic disadvantage, discriminatory policing, and systemic racism operate together as a web that traps successive generations in cycles of poverty, over-policing, and unequal justice. These aren’t accidental outcomes; they are products of historical exclusion, policy bias, and societal attitudes that continue to shape life chances along racial lines.

Addressing crime as a race issue means moving beyond punitive approaches and confronting the social and economic roots of inequality, from barriers to education and secure work, to fair housing and justice reform. It requires a national reckoning with the legacies of colonisation, segregation, and institutional bias. Ultimately, if we are genuinely committed to reducing crime and achieving justice, we must tackle the underlying racial inequities embedded in our societies. Only then can we move toward a system that offers fairness, dignity, and safety for all, not just for the majority.