The ‘90s were a time of both optimism and unease. The internet promised connection, the economy was booming, and pop culture was fueled by irony and rebellion. Yet, beneath the surface of society lay the growing fears of youth, violence, and alternative identity. Defined by its moody aesthetic, introspective sound, and embrace of melancholy, the goth subculture thrived in this era, offering young people a space for belonging and the free expression of emotion. But when the Columbine High School shooting shocked the world in 1999, a frantic media and terrified public cast goths as scapegoats, transforming a misunderstood subculture into a symbol of imagined fear.

On April 4th, 1999, students Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold carried out a planned attack at Columbine High School in which they both attended. They planted two duffel bags carrying propane bombs in the cafeteria, but when they didn’t detonate on time, the pair armed themselves with a shotgun and a rifle, and embarked on a killing spree that took 14 lives. It ended with Harris and Klebold committing suicide less than an hour after the massacre began. Video footage soon surfaced of the offenders wearing long, black trenchcoats and dark glasses, instantly tying them to the gothic. But what did the media leave out? Context—the footage was from a school project before the attack.

“I am reluctant to declare the goth panic dead:[…] it is likely that as long as there are goths anti-goth sentiment will continue.”

‘90s were a time of both optimism and unease. The internet promised connection, the economy was booming, and pop culture was fueled by irony and rebellion. Yet, beneath the surface of society lay the growing fears of youth, violence, and alternative identity. Defined by its moody aesthetic, introspective sound, and embrace of melancholy, the goth subculture thrived in this era, offering young people a space for belonging and the free expression of emotion. But when the Columbine High School shooting shocked the world in 1999, a frantic media and terrified public cast goths as scapegoats, transforming a misunderstood subculture into a symbol of imagined fear.

On April 4th, 1999, students Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold carried out a planned attack at Columbine High School in which they both attended. They planted two duffel bags carrying propane bombs in the cafeteria, but when they didn’t detonate on time, the pair armed themselves with a shotgun and a rifle, and embarked on a killing spree that took 14 lives. It ended with Harris and Klebold committing suicide less than an hour after the massacre began. Video footage soon surfaced of the offenders wearing long, black trenchcoats and dark glasses, instantly tying them to the gothic. But what did the media leave out? Context—the footage was from a school project before the attack.

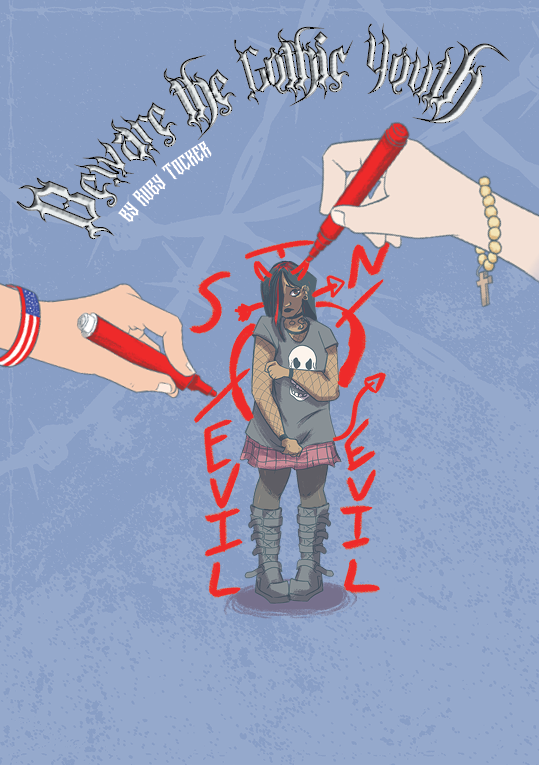

Because of this, dark clothing, eyeliner, and an iPod full of industrial rock became the signs of a budding criminal. News outlets ran with the sensationalised claims, parents panicked over their children’s playlists, and schools began policing individual expression in the name of safety. As academic Allen Berres states, these reactions were “motivated by the overwhelming fear that any member of these black-clad legions [goths] could turn out to be the next school shooter.” In reality, Harris and Klebold were not part of the goth community, but simply pathetic, performative teens with a deep desire for the attention of others. This truth was drowned out by the more alluring narrative that a liking to goth music and fashion must signal darkness in one’s soul. Journalist Marc Fisher affirmed as much in the Washington Post. He claimed that Harris and Klebold “were members of a small clique of outcasts who always wore black trenchcoats and spent their entire adolescence deep inside the morose subculture of gothic fantasy.” This blatant lie confirmed that the pair’s assumed identity was being vilified, and in conflating aesthetic rebellion with violence, the media had announced a monster was lurking on the fringes of society—beware the gothic youth!

It’s clear that Fisher, and other uninformed media men, had little knowledge on the gothic subculture. Born from the punk culture of the ‘70s and ‘80s, goths drew from Gothic literature, moody music, and dark, theatrical dress to build their aesthetic. Berres lists the bands “Sisters of Mercy, Bauhaus, Siouxsie and the Banshees, and the Cure” as sources of goth inspiration. The subculture didn’t aim to glorify violence, rather, it offered creativity, introspection, and a sense of community for those who felt alienated by the norm. At its core, being goth is about finding beauty in the macabre and curating a safe space for free expression.

Indeed, the vilification of goths was felt immediately after the Columbine shooting. Jennifer Muzquiz, a teenage goth in 1999, told CNN that her rainbow hair, face piercings, and dark dress caused her so much flak that she completed high school at home. “Parents, often successfully, lobbied to get trenchcoats and all-black attire banned in their local schools. School administrators started considering these groups to be gangs and harassment of students was rampant”, she explained. A segment on 20/20 about the evil of goth confirmed this narrative. Reporter Brian Ross told viewers “With traditional gangs, their enemies are pretty well-defined. With sub-urban groups, their enemies are not defined. I think everybody is their enemy, anybody who would gel in their way, I think they would potentially kill.” Beyond school, people would cross the street to avoid Muzquiz and her friends. Arkansas teacher Barbara Rademacher admitted that “Life was never the same after that day”, saying that “Columbine was to education what 9/11 was to the United States: a shattering wake-up call, a disaster so profound, it permanently changed our world view.” In addition to the ban on clothing and accessories, schools mandated see-through backpacks and added metal detectors to their anti-goth arsenal. It was a gross overreaction; one that permanently damned the goth subculture and those who chose to adopt its aesthetic.

And this stigma didn’t fade quickly— rather, it lingered like a bad smell. Teenagers who dressed in the goth aesthetic continued to be singled out by teachers, bullied by peers, or monitored by worried parents, as though their appearance alone predicted a criminal future. This resulted in young people abandoning their style to evade harassment, while others embraced it in an act of defiance, subverting the subculture into a form of resistance. This misrepresentation and its effects left a deep scar: goth became less visible in mainstream spaces, but grew stronger in its inner, underground circles, emphasising its reputation as a culture of solidarity and survival. In short, goth endured outside of the public eye, never quite recovering from the stain of Columbine.

Berres insists this issue is ongoing. He expresses that “I am reluctant to declare the goth panic dead; […] It is likely that as long as there are goths, anti-goth sentiment will continue.” This reveals the desperation of society to name a scapegoat in moments of fear, not only in the event of school shootings, but in tragedies of any kind. Thus, Harris and Klebold’s gothic legacy, fabricated by both the public and press, damaged an entire community and coloured over more significant issues that arose from their attack. The alienation of alternative identities, access to weapons, and systems surrounding youth were ignored in the name of a narrative that was easier to sell, but ultimately far less true, leaving the stigma of difference to fester while the root of the problem remained unaddressed. In my opinion, the horror of the Columbine High School shooting was compounded by the rush to simplify and blame, erasing nuance and silencing voices that may have offered understanding. It was a massive miscarriage of justice, and as of now, justice is yet to be served.